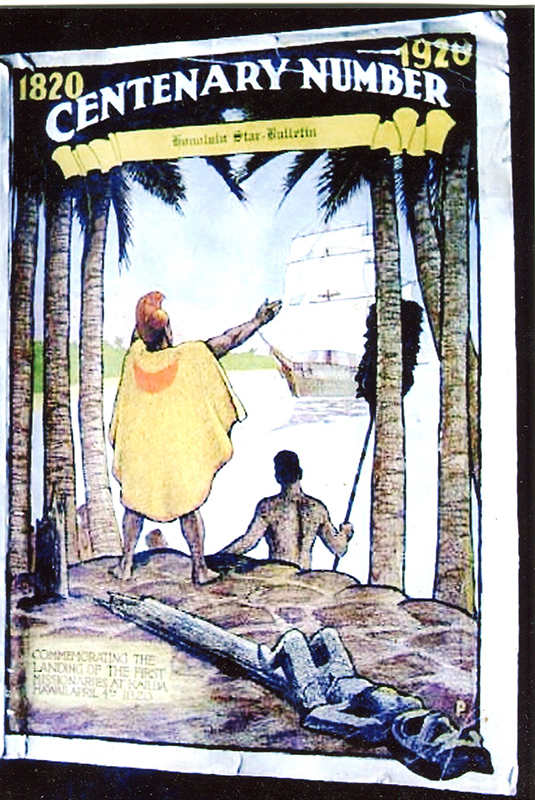

King Kaumuali‘i stood at his kauhale compound located along the shoreline just below Paulaula-Fort Elisabeth on the east side of Waimea River. Word has arrived that his long-lost son Humehume had returned. With tears in his eyes the lean but the muscular king of Kauai and Niihau intently gazed at the 100-foot long Boston brig Thaddeus anchored offshore. The date was May 3, 1820.

A scout sent out to the two-masted ship had returned at a double-beat paddle. He rushed up to the king with the unexpected news of the return of Humehume, the long-lost son of Kaumualii who had departed Kauai as a young child about fifteen years earlier.

Soon a sea captain and three young men dressed in proper western suits, one a young Native Hawaiian man, stepped ashore from the Thaddeus’ whale boat. They were George Prince Kaumualii accompanied by the Samuels, young New England missionaries Samuel Ruggles and Samuel Whitney. Although George had accompanied the missionaries, he had not embraced Christianity.

Whitney describes the arrival in the first missionary journal account ever written from Kauai.

“A salute of twenty-one guns (cannons) was fired from the brig and answered by as many from the fort. Soon after Captain Blanchard, Brother R. & myself accompanyed George to his father’s house. The King & Queen were sitting on a sofa by the door, surrounded by a large company of the principal men. The introduction was truly affecting. With an anxious heart & trembling arms, the aged Father rose to embrace his long lost son. Both were too much affected to speak. Silence for a few moments pervaded the whole, whilst the tears trickling down their…cheeks spoke the feelings of nature.”

This emotional passage marked the beginning of the missionary era of Kauai and Niihau, an islandwide movement that lasted until the early 1860s.

The way seemed to be prepared for the warm welcome given by Kaumuali‘i to the pioneer Protestant missionaries sent from Boston to Hawai‘i in October 1819 as members of the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions’ Sandwich Islands Mission. Teams of missionaries landed at Kailua–Kona on April 4 after 164 days at sea, and a few weeks sailed to Honolulu.

A year earlier, in May 1819, Kamehameha died at his Kamakahonu compound at Kailua Bay, Hawaii Island. Kamehameha had brought peace and safe passage for the Hawaiian people, and now the missionaries, by uniting the Hawaiian Islands into one kingdom through almost twenty years of warfare.

Months later his son and heir Liholiho, prodded by Kamehameha’s sacred queen, Keopuolani, his favorite and most powerful queen, Kaahumanu, and his kahuna nui, high priest Hewahewa, overthrew particularly the religious aspects of the ancient kapu system of laws that controlled most aspects of the lives of the people of Hawai‘i, specifically the Ai Kapu, which segregated women from eating with men.

The collapse of the kapu system led to the abandonment of all heiau temples in Hawaii. The stone and wooden images of Hawaii’s gods were destroyed or secreted away. Kaumualii told the American missionaries that just months prior to their arrival in May 1820 he gladly overturned the old religion.

Whitney’s account of meeting Kaumualii, whom he knew as Tamoree, portrays him sharing his breath with Kaumualii (the Native Hawaiian cultural greeting known as honi). This goes against the stereotype of the American missionaries as stodgy Calvinists unaware of the ways of Hawaii.

“We were introduced to Tamoree, as persons who had left our native country & had come to reside at the Islands for the purpose of instructing the natives. They then joined noses with us and said it is good, I am glad to see you. A table was soon set in very good stile, and we were invited to sit down to dinner. In the evening a house was prepared for Brother R. and myself, & we retired much pleased with the prospect of usefulness.”

The missionaries, when not seasick, daily studied the Hawaiian language except Sunday during their voyage from Boston. At their first landing, at Kawaihae Bay on Hawaii Island, the Thaddeus Journal notes missionary wives conversing in Hawaiian phrases with Kalanimoku, the prime minister and lead general of Kamehameha.

Ashore on Kauai, George Prince Kaumualii rediscovered his Hawaiian name, Humehume, a name he had lost to memory over his years of life in New England and at sea as a marine during the War of 1812.

Ruggles and Whitney presented Kaumualii a special English language Bible sent by the American Bible Society at the request of George. The name “Tamoree” spelled out in gold leaf letters decorated the cover of the large Bible.

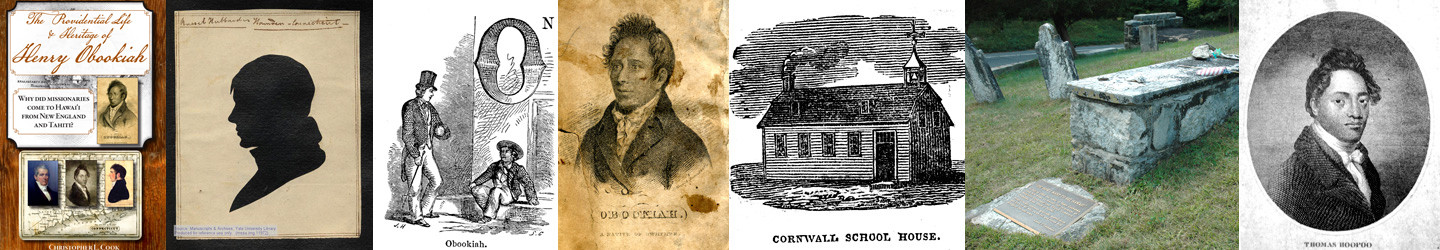

As George Prince, his son had been given a home and a future in 1816 after being found aimlessly living at the Charlestown Navy Yard in Boston. George dwelled in despair; a homeless teenage combat wounded marine returned from the War of 1812.

Leaders in the American missionary movement provided support for the young prince’s education at the American Board’s Foreign Mission School in Cornwall, Connecticut. There he excelled in astronomy and learned to play the bass viol.

Missionary teacher Samuel Ruggles arrived at Waimea already accustomed to Hawaiian ways and life among Native Hawaiians. He had befriended George at Cornwall. For over two years Ruggles lived, studied, socialized, and worked in the fields and forests of Cornwall with George, Opukahaia (Henry Obookiah), Thomas Hopu and other Native Hawaiian students.

Whitney and Ruggles returned to Honolulu with a promise from Kaumualii of land for a mission station and full support for holding church services and teaching reading and writing.

In late July 1820 the men returned with their wives to open a mission station at Waimea.

Mercy wrote in her journal: “George came to the Vessel to see if we were on board, & then sent for his parents who immediately came in a double canoe.”

A great crowd gathered at Waimea on Kauai’s westside to greet the missionary couples to see the first white women to settle on the island.

Nathan Chamberlain, the young son of missionary farmer Daniel Chamberlain, accompanied the missionaries, serving as translator. During the long Thaddeus journey the Chamberlain children quickly picked up the basics of the Hawaiian language by conversing with George, and the three Native Hawaiian missionary assistants aboard.

The Whitneys and the Ruggles soon experienced the ways of Kauai when its population was almost all Native Hawaiians. They slept on layers of kapa cloth, attended a hula performance, listened to drumming and chanting, and adapted to eating local foods.

The first Christian church service ever held on Kauai began at 10 o’clock on Sunday morning July 30. The missionaries joined by a visiting sea captain led the service in a makeshift chapel erected along the makai side of the fort at Waimea.

The Kauai missionaries faced a daunting task.

Their overarching mission was to spread Christianity. In accomplishing this they were greatly aided in advance when a spiritual vacuum was caused six months earlier by the abandonment of the kapu system.

They saw an immediate need to support Native Hawaiian family life and introducing western medicine with hopes of turning around the drastic decline in the Hawaiian population that had dropped as much as eighty percent from the arrival of Captain Cook in 1778 to the arrival of the missionaries to Hawaii in 1820.

The first laws printed in Hawaii sought to preserve the Hawaiian people. By 1825 Queen Regent Kaahumanu, Kalanimoku and other alii nui had become practicing Christians. Kaahumanu based these first printed laws on the Ten Commandments. She primarily sought to end the rampant prostitution of Hawaiian women to visiting the dozens of shiploads of sailors then arriving in Hawaii ports. And to control the heavy drinking at grog shops that catered to these sailors. A violent reaction resulted in attacks on the missionaries by sailors.

Within a generation the Kauai missionaries more than accomplished their goals.

Literacy and education spread to every village in Kauai. Native Hawaiian students trained to be teachers of the palapala; the written word taught through a biblical-based curriculum as its foundation. Students who excelled were trained to teach others and moved on to other villages. By the 1850s these palapala schools ringed Kauai even opening at remote Kalalau and Milolii valleys. The literacy rate in Hawaii rose to first place in the world.

Mission stations opened at Koloa and Waioli at Hanalei. Queen Deborah Kapule founded a church along the Wailua River near Coco Palms with services held in the Hawaiian language.

From printing presses in Honolulu and Lahaina millions of pages in the written Hawaiian language were distributed. The development of a written Hawaiian language, and translation of the complete Bible directly from biblical languages was completed in 1838. The American missionaries worked closely with Native Hawaiian and Tahitian scholars in creating the Bible. The written Hawaiian language flourished in the nineteenth century through a wide variety of Hawaiian language newspapers all tracing their roots back to the first printing in the Hawaiian language at the mission press in Honolulu in 1822.

Missionary doctors combated the introduced diseases traditional kahuna healers could not cure. In 1853 Dr. James Smith of Koloa, the first western doctor stationed full time on Kauai, inoculated almost every person on Kauai and Niihau keeping away from the shores of Kauai a smallpox epidemic that killed thousands of Native Hawaiians on Oahu and other Hawaiian islands.

Melodious western music caught the ear of the people of Hawai‘i through missionary “singing schools” and the first book ever published in the Hawaiian language was a hymnal that included hymns in Tahitian brought by Tahitian Christians in 1822.

The Sandwich Islands Mission officially ended in 1863 with orders from Boston to encourage Native Hawaiian ministers to become pastors of the churches founded by the American missionaries. Today many of those churches still flourish on Kauai.

For updates on future Kauai Missionary Bicentennial events go to www.missionhouses.org/bicentennial