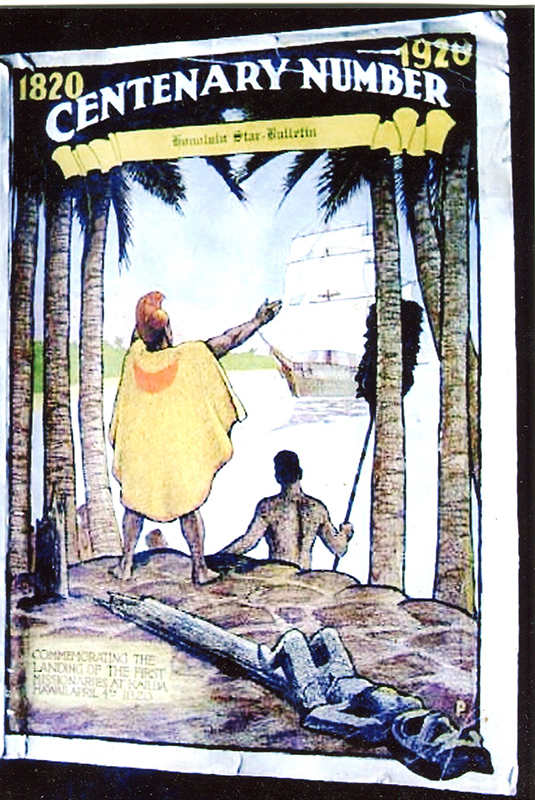

Cover of oversized Honolulu Star-Bulletin special publication Century Number “Commemorating the Hundredth Anniversary of the Landing of the First Amerian Missionaries in Hawaii” at Kailua Hawaii April 4th 1820, published April 1920 in Honolulu. The illustration shows the brig Thaddeus arriving at Kailua, Kona on April 4th, 1820 and an ali‘i wearing a feathered cape greeting the missionary party aboard with open arms.

In late November 1819, two Boston sea captains carried to O‘ahu and Kaua‘i orders from Liholioho, Kamehameha II, to destroy the heiau [temples] and the ki‘i [stone and wooden images], according to a first-hand account given in Boston in 1820 by captains Blair and Clark. This sensational report appeared in the July 1820 issue of the Panoplist & Missionary Herald, the monthly missionary and revival publication of the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions.

“Captains Blair and Clark left Owyhee about the 25th of November [1819], and carried down to Woahoo [O‘ahu] and Atooi [Kaua‘i] the king’s orders to burn the monuments of idolatry there also. The order was promptly obeyed in both islands. In Atooi the morais and all the consecrated buildings, with the idols, were on fire the first evening after the order arrived. The people of all these islands had heard what had been done at the Society islands; and there is no doubt that Providence made use of this intelligence to prepare them for so wonderful a change. Captain Blair informs us, that a native chief, named Tiamoko [Keeaumoku], called by Americans Governor Cox, has been for some time inclined to speak very contemptuously of the whole system of idolatry. He was the chief man in the island of Mowee.”

[Note: Captain George Clark master of the Boston ship Borneo, shipwrecked at Kaigani, Alaska in January 1819. Clark and his crew then sailed to Hawai‘i aboard the brig Brutus, Captain Nye. Clark and Blair may have been on the same ship, sailing from Kailua, Kona carrying the orders of Liholiho for O‘ahu and Kaua‘i.]

Following is a copy of the complete report published in the July 1820 issue of the Panoplist & Missionary Herald detailing the overthrow of the kapu system at Kailua, Kona in fall 1819, six months following the death of Kamehameha at Kailua, Kona, and about six months prior to the landing of the pioneer Sandwich Islands Mission company sent from Boston in October 1819.

From the Panoplist & Missionary Herald July 1820 pp. 334-336

For several years past, the Sandwich Islands have presented objects of great curiosity to the inquisitive philanthropist. Since a Christian mission from this country to these islands has been contemplated, and especially since the sailing of the missionaries last October a general interest has been felt with respect to every thing, which relates to the civil policy, and present condition of the natives; as the reception of our brethren might be much affected by these things.

When the Thaddeus sailed, intelligence had not been received of the death of the old king Tamaahmaah, though such an event was considered as likely to take place soon. The life and activity of this man, his acquisition of property and power, and the order and subordination which he had enforced, have for many years attracted no small attention in Europe and America, and his name frequently appears in English reviews. We have conversed with many captains and others, who had been long particularly acquainted with him They united in declaring, that he was a man of extraordinary talents; and that, with superior advantages, he might have made a great statesman. He was very fond of property, and of commerce as the means of obtaming it. Towards the close of life his avarice became more in. tense, as is generally the case with avaricious men, in all parts of the world. He hoarded Spanish dollars, and almost every kind of personal property, which was not immediately perishable. He had large stone-ware-houses filled with drygoods, axes, hoes, fire-arms, and other instruments of defence and offence. He had a fort, with guns mounted, and sentinels regularly on duty. He owned three brigs, a schooner, and several small craft. His control over the persons and Property of his subjects was absolute. To maintain this control it was a part of his policy to keep them poor and dependant, and to exercise his power continually. To his chiefs he granted certain privileges. One of them named Krimakoo [Kalanimoku], was always called his prime minister by the English and Americans, and was by them nicknamed Billy Pitt. He is described by all as being an able, intelligent, and faithful agent. The principal queen is also said to be a shrewd sensible woman, and to have exerted great influence. The late king was the high priest, an office which he assumed many years ago, to obtain and secure his political authority. He was very strict in the performance of his sacerdotal functions, though it is supposed that the ceremonies of his religion were perfectly unintelligible even to the natives, and that he had no sort of confidence himself in the system.

Tamaahmaah was a strong athletic man till near the close of life, when he became quite emaciated, and died of a gradual decay. He was apprehensive of his approaching dissolution, appointed his only remaining son to succeed him, established his chiefs in their accustomed privileges, associated Billy Pitt and the principal queen with the young prince as advisers, and left the world without any fear that the succession would be disturbed. His subjects made a great lamentation over him, and many of them have these words tattoode, that is pricked into the skin of their arms and breasts with indelible ink, in large Roman letters: our GREAT AND GOOD KING TAMAAHMAAH DIED MAY S, 1819. The age of the old king is supposed to have been about 70; the young king is about 23. His name is Reeho-reeho, and he has assumed that of his father.

The preceding facts are stated as introductory to others of a much more interesting nature, and which seem to have a most auspicious bearing on the mission, which left our shores attended by so mamy prayers, and has been the object of so much affectionate solicitude.

Early in the month of November, the young king, (who had himself been inducted into the office of high priest before his father’s death with a view to preserve his political influence), came to the resolution to destroy the whole system of idolatry. It was supposed that this was done with full deliberation, with the consent of all who had any voice in the government, and without any opposition from the people. With respect to these transactions, we have the most explicit statements from two eye-witnesses, masters of vessels, who have long been conversant with these islands, captain Blair, and captain Clark, both of Boston. When the resolution was taken, orders were issued to set the buildings, and inclosure consecrated to idolatry, on fire; and while the flames were raging, the idols were thrown down; stripped of the cloth hung over them, and cast into the fire; and, what is still more marvellous, the whole taboo system was destroyed the same day. The sacred buildings were, some of them, thirty feet square. The sides were formed by posts 12 or 14 feet high, stuck into the ground, and the intervals filled with dry grass. The roofs were steep, and thatched with grass, in such a manner as to defend from rain. The morais [heiau] or sacred inclosures, were formed by a sort of fence, and were places, where human sacrifices were formerly practised. Before these inclosures stood the idols, from 3 to feet high, the upper part being carved into a hideous resemblance of the human face.

The taboo system was that, which was perpetually used to interdict certain kinds of food, the doing of certain things on certain days, &c. &c. in short to forbid whatever the king wished not to be done. On some subjects the taboo was in constant operation, and had been, very probably. for thousands of years. It forbade women and men to eat together, or to eat food cooked by the same fire. Certain kinds of food were utterly forbidden to the women; particularly pork and plaintains, two very important articles in those islands. At the new moon, full, and quarters, when the king was in the morai, performing the various mummeries of idolatry, it was forbidden to women to go on the water. Every breach of the taboo exposed the delinquent to the punishment of death. But so well was the system understood by the people, and so great was the dread of transgression, that the taboo laws were very rigidly observed. We have said, that the taboo system has probably been in operation thousands of years. Our reasons for thinking so are these. The same system pervailed in the Society Islands, at the distance of three thousand miles nearly, and in New Zealand, at the distance of five thousand miles; while the New Zealanders have been so long seperated from the Sandwich Islanders, that the languages of the two classes of people have become exceedingly different. The inhabitants of these remote islands probably never had any communication with each other till very recently, and now in European and American vessels only. But they must have decended from the same race of men, after the taboo system had been formed and was in full opperation. This must have been long ago; but how long it would be useless to conjecture.

Captains Blair and Clark left Owyhee about the 25th of November [1819], and carried down to Woahoo [O‘ahu] and Atooi [Kaua‘i] the king’s orders to burn the monuments of idolatry there also. The order was promptly obeyed in both islands. In Atooi the morais and all the consecrated buildings, with the idols, were on fire the first evening after the order arrived. The people of all these islands had heard what had been done at the Society islands; and there is no doubt that Providence made use of this intelligence to prepare them for so wonderful a change. Captain Blair informs us, that a native chief, named Tiamoko [Keeaumoku], called by Americans Governor Cox, has been for some time inclined to speak very contemptuously of the whole system of idolatry. He was the chief man in the island of Mowee. The chiefs and people in all the island expressed a desire that missionaries might arrive, and teach them to read and write, as the people of the Society Islands had been taught. Tamoree, king of Atooi, and father of George [Humehume, George Prince Kaumuali‘i], who went with the missionaries was particularly desirous that teachers should arrive. He was very anxious to see his son and has sent one of his subjects, by a vessel now on her way from Canton to Boston, with an express order for George to return. He had also manifested a great wish to visit Pomarre [Pomare II], at Otaheite, and see for himself the change that had taken place there.

Both captain Blair and captain Clark, who have been acquainted with these islands for more than 20 years, and are confident, that the missionaries will be joyfully received by the natives: that now is the very time for their arrival; and that their services are peculiarly necessary to introduce the truth after the destruction of idolatry.

It is hoped that the missionaries arrived and were landed at least two months ago. What trials, or what encouragements, they have met with, we know not. To the care and direction of a merciful Providence let them be commended daily by all the friends of missions.