In 1858 the Rev. Jonathan Green, Kahu of the Po‘okela Church in Makawao, Maui, a native Hawaiian church he organized, wrote a letter back to his homeland in New England describing the celebration of Thanksgiving in Hawai‘i. The letter appeared in the July, 1859 issue of the New England Farmer magazine.

EDITORS FARMER:-Gentlemen, Reminded by the closing year of my delinquency in writing you, I hasten to devote a part of this day of public thankagiving to this purpose. The occasion will suggest a subject of interest to you and your readers, as Thanksgiving day, though at a distance, will remind them of scenes in which they all delight to participate.

“Hawaiian Thanksgiving !” do I hear you exclaim? with the remark, “You can be as thankful, certainly, as any of us, and God, who is no respecter of persons, will accept your gratitude. But as for the Thanksgiving supper, with tables groaning with New England luxuries, around which gather hosts of friends, this, of course, you know nothing about. A dish of poi and a baked dog or raw fish spread on a clean mat, or on some fresh ferns, will doubtless constitute your Thankgiving repast.” Well, friends, I mean to take in good part this specimen of banter which I have supposed you might employ when hearing that the king and chiefs of Hawaii are so far adopt ing the customs of New England, as to appoint a day of thanksgiving and prayer to God, for His kindness to the nation during the past year. Nor will I deny that both chiefs and people are calculating somewhat largely on thrusting their fingers into the poi dish, and thence to their mouths, ere the day closes; nor do I doubt that many a fat and sleek animal of the canine species is now in an oven of hot stones remunerating in part the expense of feeding. I am not horrified in relating, and I hope you will not be in hearing, that dogs are often strangled and eaten by chiefs and people. Foreigners, generally, universally perhaps, cry out, shame, shame, at the practice. I know not that any of them, knowingly, eat of this dish, though I shrewdly guess that more than one gentleman from en lightened lands when dining with the chiefs of Hawaii, have eaten with a gusto from a creature! whose vernacular was bow-wow, instead of baa, as they supposed. I know not as I have ever tasted dogs’ flesh. I have no particular desire to do so. Still, I see no moral wrong about it, nor do I feel like dissuading my people from such a practice. De gustibus non disputandum est, or, let there be no disputing about tastes, is a maxim which is worthy of consideration. Most heartily do I wish that the men from our country would do nothing worse than eat dogs’ flesh.

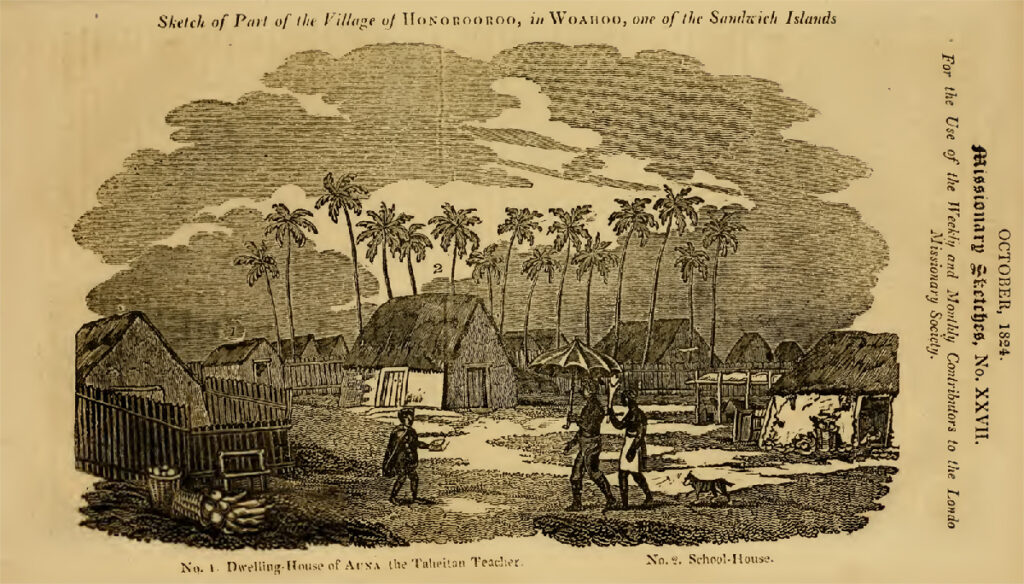

But to return to the subject of Thanksgiving supper, which seems to be a sine qua non in the idea of a Puritan Thanksgiving. I am glad that you feel a doubt of our ability to get up a supper on this occasion, which will at all compare with yours, as in laboring to remove this doubt, shall be able to tell you of the change in our circumstances since March, 1828, when, as one of the second reinforcement, some eight years after the establishment of the mission, I landed at Honolulu.

At that time there were no Thanksgiving days appointed by the government, and had there been we could not have got up much of a supper. Our four was very poor, sour, and often musty. Butter and cheese, fresh beef and mutton we rarely tasted. Salmon from Oregon we could obtain, but without Irish potatoes and butter, this scarcely relished. Molasses we used for our tea and coffee. We had an occasional fowl, but as we bought them of the natives, they were lean and unsavory. Of vegetables we had kalo and sweet potatoes-of fruit, bananas or plantains-also, melons. These were our facilities in 1828 for getting up a Thanksgiving supper. In 1829 no flour having arrived from Boston, there was much suffering in the Mission families at Honolulu, and the health of not few individuals was greatly affected. Since that time there has been a gradual improvement in the means of living so that to-day, we can have a Thanksgiving supper purely Hawaiian, composed of the following dishes, viz.: Baked beef and lamb, both beautifully fat and tender, and good enough for John Bull himself; fine large and fat turkey and baked fowl; excellent mullet from fresh water ponds; roasted pig fed on milk, ten der and savory; potatoes, both Irish and sweet ; kalo, of which the poi is made, but which boiled or roasted is excellent; bananas or plantains cooked in almost as many ways as your apple, and, on the whole, an excellent substitute; bread fruit, onions, beans and lettuce, Indian corn, tomatoes and cabbage. To these vegetables, there can be added at some of our stations, turnips, beets and carrots. Bread, of course, at Makawao, must not be forgotten. This we have plentifully, made of coarse meal ground in our hand mills or fine bolted at our steam mill at Honolulu. With these ingredients we can have chicken pie; also, custards, as sugar, eggs and milk are abundant; pumpkin and banana pies like wise. Butter and cheese, with fig, guava and olelo-Hawaiian whortleberry-preserves. Pia or arrow-root puddings, Hawaiian coffee with cream and sugar. A part or all of these we can furnish for our supper this evening also melons, oranges, guavas and figs. Or if our friend, Dr. Alcott, will sup with us, be shall have good baked potatoes and bread, pia, also, with figs and oranges. Please recollect, gentlemen, that I did not spread this table to cause a surfeit, but to show you what a change the blessing of God on industry has wrought in our circumstances of living since 1828.

Evening.-I have just returned from the house of God, where I addressed our people on the goodness of their heavenly Benefactor during the year which is near its close. It has been, on the whole, a year of prosperity to the Hawaiian nation. Health has prevailed as a general thing. Peace has blessed the nation with its balmy influence. The earth has yielded her usual increase, so that to-day we may justly speak of the watchful care of a benignant Providence, and of the loving kindness of God to us all. In addition to the products of the earth purely Hawaiian, there have been sown and reaped a larger number of acres of wheat in this district than ever before, and though a good deal of this was destroyed by the caterpillar, still some 16,000 bushels were secured and sold, besides a good deal reserved for seed. Considerably many oats were raised, also corn and beans. Besides these essentials, the islands are fast developing their capabilities of producing fruit. Oranges are becoming increasingly plenty. Peaches, also, will soon become abundant. Figs have long been so, also guavas and custard apple. I have not doubt that Hawaii will become famous as a fruit growing country. In this prospect I greatly rejoice, and I am exhorting the people to turn their attention more to fruit-growing. Oranges and figs eaten freely would conduce much to the physical health and enjoyment of all classes among us. Some of them are beginning to think more favorably of this department of labor and enterprise. The growing of wheat, however, at present secures most of their attention. Though It is not a very profitable branch of enterprise still multitudes wish to try their hands at it, and as the Hawaiian Steam Flouring Company pay cash for wheat, an increasing number are thrusting in the plow, and scattering the seed over the furrowed fields. One benefit the people are certainly deriving from the introduction of wheat into their country,-they are forming habits of industry. In this I greatly rejoice. Of the success of their labors I will tell you in my next communication.

Yours with respect, J. S. GREEN