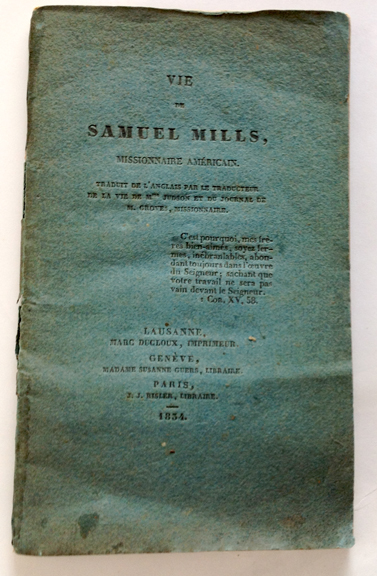

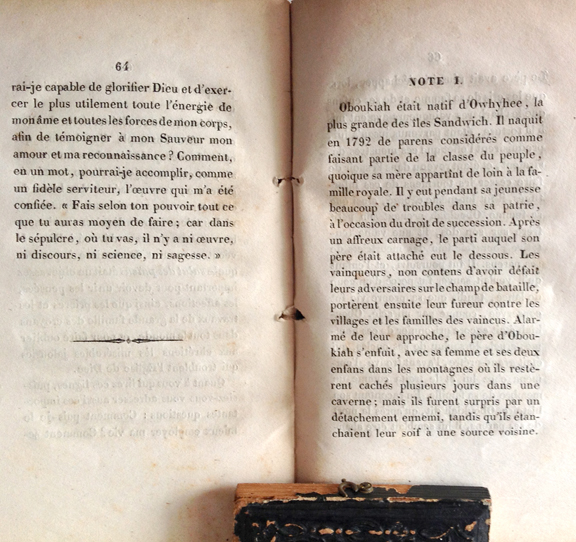

Vie de Mills Missionnaire Américain is a booklet published in 1834 out of Switzerland. The life of Samuel Mills Jr., the leader of the famed Haystack Meeting that launched American foreign missions, is told in the booklet. A brief life of Opukaha‘ia is appended to Mills’s life. There is an online version of Vie de Mills Missionnaire American. I was able to locate a copy of this rare and obscure publication out of the home of John Calvin in a book store located in Barcelona, Spain. The wonder of the World Wide Web! No new information is included in Vie de Mills Missionnaire American, but discovering the story of Obookiah in French shows additional evidence of how widespread the fame of Obookiah’s story was in the 19th century.

Christian History of Hawai‘i

Hana Hou Tour coming to Big Island

I am joining Dave Buehring’s Hana Hou Christian Heritage Tour on the Big Island from Saturday, February 13-16, 2016. I will be an interpretive guide for the visitors from the Mainland coming to Hawai‘i to visit key sites in the life of Opukaha‘ia. Opukaha‘ia’s descendant Deborah Lee, who led in the return of Henry’s remains in 1993, will also being serving as interpretive guide on the tour.

Local residents are invited to join the tour. Go to www.hanahou.info for more information. Those accompanying the tour are asked to share in covering the costs for the joint meals being provided.

The tour schedule includes a visit to Hikiau Heiau on the shore of Kealakekua Bay and Henry’s grave site at the Kahikolu (Trinity) Church on Saturday, February 13.

On Sunday, February 14 the tour moves to the Mokuaikaua Church, home of Hawai‘i’s oldest existing Protestant church, and a look at the Plymouth Rock of Hawai‘i sign at the Kona Pier. I helped write the text of the new sign, posted to mark the 195th anniversary of the Mokuaikaua Church. Will be interesting to see the historic signage in person.

On Sunday, February 14 the tour moves to the Mokuaikaua Church, home of Hawai‘i’s oldest existing Protestant church, and a look at the Plymouth Rock of Hawai‘i sign at the Kona Pier. I helped write the text of the new sign, posted to mark the 195th anniversary of the Mokuaikaua Church. Will be interesting to see the historic signage in person.

On Monday, February 15 we head to Punalu‘u Beach in Ka‘u to visit the chapel dedicated to Henry. His birthplace and childhood home were at Ninole, the land section on the south end of Punalu‘u Beach. Then the tour bus will travel north to Volcano National Park to revisit the site of early Native Hawaiian Christian and alibi Kapiolani’s defiance of the goddess Pele in the 1820s.

Tuesday, February 16 the tour ends at Haili Church in downtown Hilo. Here I will join Deborah Lee at her family’s home church when we join a panel discussion on the impact of the American Protestant Mission in Hawai‘i. The roots of the Haili Church go back to Hawai‘i’s Great Awakening in the late 1830s. The Rev. Titus Coan from Connecticut led the Sandwich Islands Mission station in those days. Native Hawaiian became Christians by the hundreds and thousands in the late 1830s, and the Hilo congregation grew to about 12,000; the church was declared to have the largest congregation in the entire Protestant world.

Tahitian connection

In the chapter “Tahitian Connection” in my book The Providential Life & Heritage of Henry Obookiah I detail the influence of the Tahitian church in the coming of the Gospel to Hawai‘i as seen through the eyes of the America’s foreign mission movement led by the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions.

As often happens when sending a book to print, new information soon after appears. Here are copies I have recently acquired of items published in contemporary missionary publications in the 1820s that tell of this Tahitian connection.

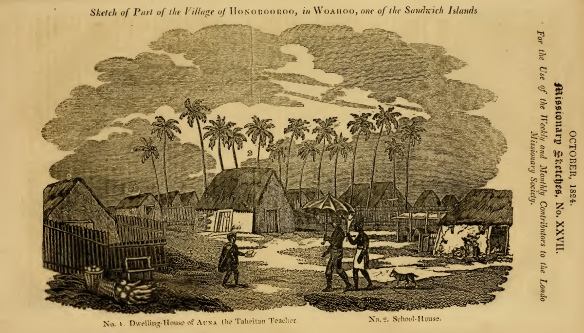

From the London Missionary Society’s Missionary Sketches, a pamphlet-size publication regularly distributed to supporting members of the London Missionary Society, from 1824. Here is the only known illustration of the work of Auna, the Tahitian missionary and teacher who arrived in Hawai‘i in 1822. Auna, a Tahitian ali‘i, opened a school in a large thatched hale located near Honolulu Harbor.

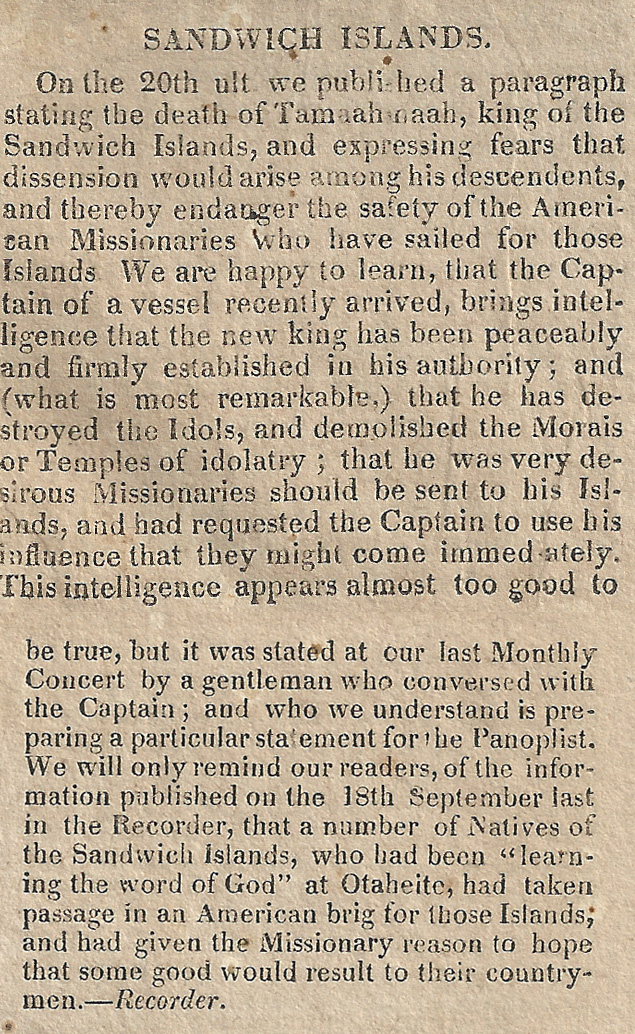

These comments appeared in late 1820 and early 1821 issues of the Religious Intelligencer, a weekly newsprint missionary and revival-focused publication from New Haven, published and edited by Nathan Whiting. One of the accounts came from the pages of the Boston Recorder, a prominent Christian newspaper in its day.

Below is another account from the Religious Intelligencer, written from the viewpoint of the New Haven publication in 1820.

Captain Cook’s Atooi = And Tauai

The Rev. William Ellis of the London Missionary Society is arguably the leading non-Native Hawaiian chronicler of Hawai‘i in the first half of the 19th century.

There are gems tucked away in Ellis’ books that clarify points of Hawai‘i’s history that have surfaced and been sometimes used inaccurately in the 21st century.

One is the pronunciation and source of the place name Atooi, as recorded in the journals of Royal Navy Captain James Cook. Atooi is how Cook heard Kaua‘i Island named by Native Hawaiians he and his crew encountered in landing at Waimea, Kaua‘i in early 1778.

On Kaua‘i today you hear Cook’s word Atooi pronounced Ah-too-ee, likely due to those speaking the place name employing Hawaiian language pronunciation for the vowels in the word. However, in recording the place name for Kaua‘i, Cook used straight English language pronunciation. According to Ellis the place name as heard by Cook was a compound word; A (the “A” translated as the conjunction “and”) Too-i, the “i” as in the word “idea”. The letter “T” was commonly used on Kaua‘i before the Sandwich Islands Mission codified the Hawaiian language, replacing the “t”mostly used in the dialect of the leeward islands with the letter “k”, a letter used in the windward islands. For example, Tamehameha became Kamehameha.

Here’s what Ellis wrote about the meaning and pronunciation of Cook’s word Atooi. Ellis recorded this in the 1832 edition, Hawai‘i volume, of his book series Polynesian Research During a Residence of Nearly Eight Years in the Society and Sandwich Islands:

“Another cause of the incorrectness of the orthography of early voyagers to these islands, has been a want of better acquaintance with the structure of the language, which would have prevented their substituting a compound for a single word. This the case in the words Otaheite, Otaha, and Owhyhee, which ought to be Tahiti, Tahaa, and Hawaii. The O is no part of these words, but is the preposition of, or belonging to; or it is the sign of the case, denoting it to be the nominative, answering to the question who or what, which be O wai?….

…Nom. O wai ia aina?—What that land?

Ans. O Hawaii :—Hawaii.…

“Atooi in Cook’s Voyages, Atowai in Vancouver’s, and Atoui in one of his contemporaries is also a compound of two words, a Tauai, literally and Tauai. The meaning of the word tauai is, to light upon, or to dry in the sun; and the name, according to the account of the late king (Kaumuali‘i), was derived from the long droughts which sometimes prevailed, or the large pieces of timber which have been occasionally washed upon its shores. Being the most leeward island of importance, it was probably the last inquired of, or the last name repeated by the people to the first visitors. For, should the natives be pointed to the group, and asked the names of the different islands, beginning with that farthest to windward, and proceeding west, they would say, O Hawaii, Maui, Ranai, Morotai, Oahu, a (and) Tauai: the copulative conjunction preceding the last member of the sentence would be placed immediately before Tauai; and hence, in all probability, it has been attached to the name of that island, which has usually been written, after Cook’s orthography, Atooi or Atowai, after Vancouver.

“The more intelligent among the natives, particularly the chiefs, frequently smile at the manner of spelling the names of places and persons, in published accounts of the islands, which they occasionally see.”

Source: Ellis, William. 1831. Polynesian researches during a residence of nearly eight years in the Society and Sandwich Islands. London: Fisher, Son & Jackson. pp. 51-53.